THE HERESY OF CONSCIENCE

I’ve got three pop quiz questions for you on conscience:

If your conscience thinks something is a mortal sin that is not actually a mortal sin, does that make it a mortal sin for you to do?

If your conscience thinks something is a venial sin that is actually a mortal sin, does that make it a venial sin for you to do?

Can you explain why or why not you answered what you did for the first two questions?

We have four possible responses to these questions:

First, in our modern world, the majority of people think the answers to the first two questions are “yes” & “yes”. They think that whatever the conscience says goes, no matter what.

Second, some portion of people would be in profound error and say the answers to the first two questions are “no” & “yes”. That is, if you think something’s a mortal sin but it’s not, you’re excused for doing it—but if you think it’s a venial sin and it’s actually mortal, then the truth does not prevail, but you’re excused. For these people, it’s not whatever the conscience says goes, it’s whatever creates the least amount of guilt possible goes. People in this group likely don’t have an express conception of conscience, they’re just universalists and think everyone’s saved so effectively they fall into this camp—making nothing ever a mortal sin.

Third, and I don’t know if this group of people exists, but they would answer the first two questions “no” & “no”. These would be people that effectively don’t think conscience is a thing or that it has any effect on our moral actions one way or another. Maybe casual Jansenists (Catholic puritans) would be in this group—but even that, I’m just kidding, I don’t think there’s anyone actually in this camp.

And then fourth, some portion of people would be correct and answer the first two questions as “yes” & “no”. I would suspect that the majority of my auidence would be in this camp, but I don’t know that they’d be able to explain it well. Nor do I suspect that they’d be able to articulate it in a way that would illumine why most people erroneously answer with the majority first group, when in fact they should be responding with this fourth group. Nor do they likely know that we have direct quotes from St. Thomas unequivocally articulating this fourth position.

In this article I’m going to explain why this fourth position is right, why the first position is wrong, why I think so many people are in error on it, and why I think this is the most significant heresy of our modern time.

CONSCIENCE

What is conscience? Let’s start here.

The technical definition for conscience is essentially: “an act of the practical reason applying the universal moral law to a particular action.” That is, conscience is when we take our personal understanding of the moral law and apply it to a given action.

Our conscience tells us that we think something in particular that we’ve done is wrong or right.

Say you (1) ate a bunch of junk food, or (2) ate animal meat, or (3) got drunk, or (4) microdosed LSD, or (5) married a guy as a guy, or (6) advocated for expanded access to abortion, or (7) used contraception to avoid having kids at a given time—in each of these scenarios, your conscience tells you that what you are doing is legitimate or illegitimate, right or wrong, and this is based on your personal understanding of morality.

Your neighborhood hipster, dink, or yuppie, would probably say something like, (1) is fine, (2) is bad, (3) depends on whether you can handle alcohol or not and keep your job and attend to your friendships, (4) is good and progressive, (5) is obviously good, (6) is heroic, and (7) is mature and responsible.

Your neighborhood Thomist or Liguorian Catholic would probably say something like, (1) is roughly fine, (2) is acceptable except on obligated days of abstinence, (3) is bad, (4) is an insane instance of modern human hubris, and bad, (5) is bad, disordered, and an offense againt the institution of marriage, (6) is inhumane and evil, and (7) is bad, disordered, and you’re voluntarily under the authority of Asmodeus, the principal demon of Lust.

In each case we have conscience at work doing what it does: judging whether things are good, permissible, or bad, and to what degree they’re bad—seriously bad or trivially bad.

CONSCIENCE BINDS BUT DOES NOT LOOSE

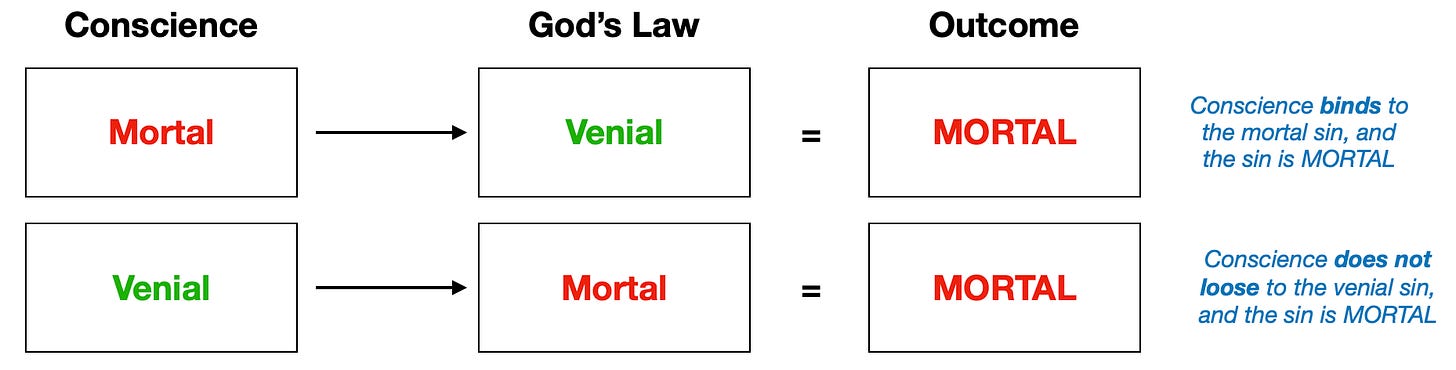

The key to understanding conscience with clarity is to understand this simple assertion: conscience has the power to bind but not to loose.

When we say that conscience has the power “to bind”, we mean that conscience can make something a more serious sin when in truth it is a more trivial sin. When we say that conscience does not have the power “to loose”, we mean that conscience can not make a sin more trivial that is in truth more serious.

That is, conscience does not go both ways. It can only make things more serious, it cannot make things less serious. This is the key to understanding conscience with clarity. As St. Thomas says:

It is said improperly that someone intends to sin mortally or venially, for evil is beyond intention and will. […] But someone intends to do something which he believes to be mortal sin, and from this it is said that he intends to sin mortally. Therefore, the aforesaid question seeks nothing except why someone believing what he does to be mortal sin, sins mortally. Yet it is not necessary that it be venial if he believes it to be venial, such as if he believes fornication to be a venial sin. (QL VIII:6:v:resp) (My emphasis.)

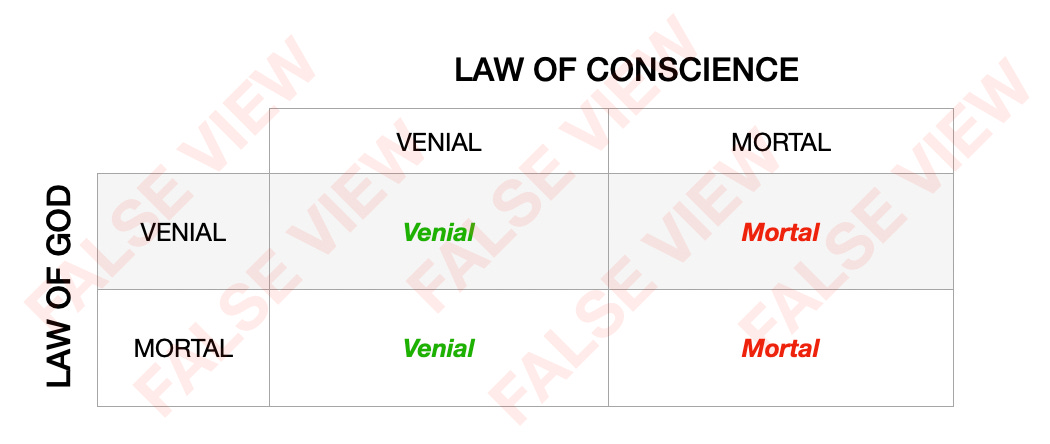

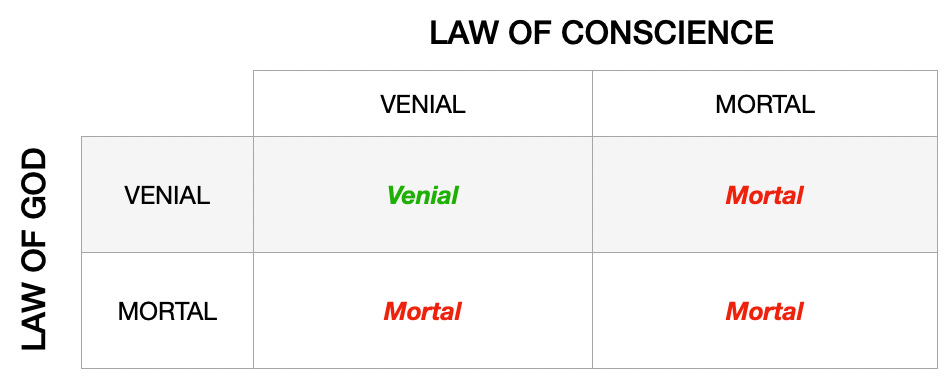

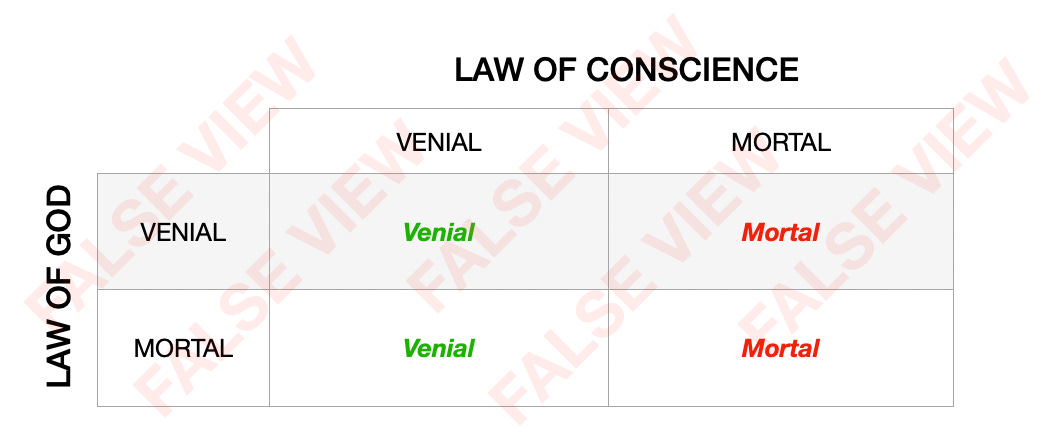

The following chart shows how the interaction between the Law of Conscience and the Law of God works:

Most of our Church today is in error because they think the Law of Conscience is “absolutely sovereign”, and imagine the interplay between the Law of Conscience and the Law of God to be instead like this:

Conscience can never be “absolutely sovereign” because it’s always bounded from above (God). Any created sovereignty is automatically limited by what it’s been given sovereignty over from God. Only God has purely absolute sovereignty.

THE SOURCE OF THE ERRORS

The main question we have to answer, then, is how people have gotten this so wrong? And if it’s so clear, why hasn’t this understanding proliferated in our Church today?

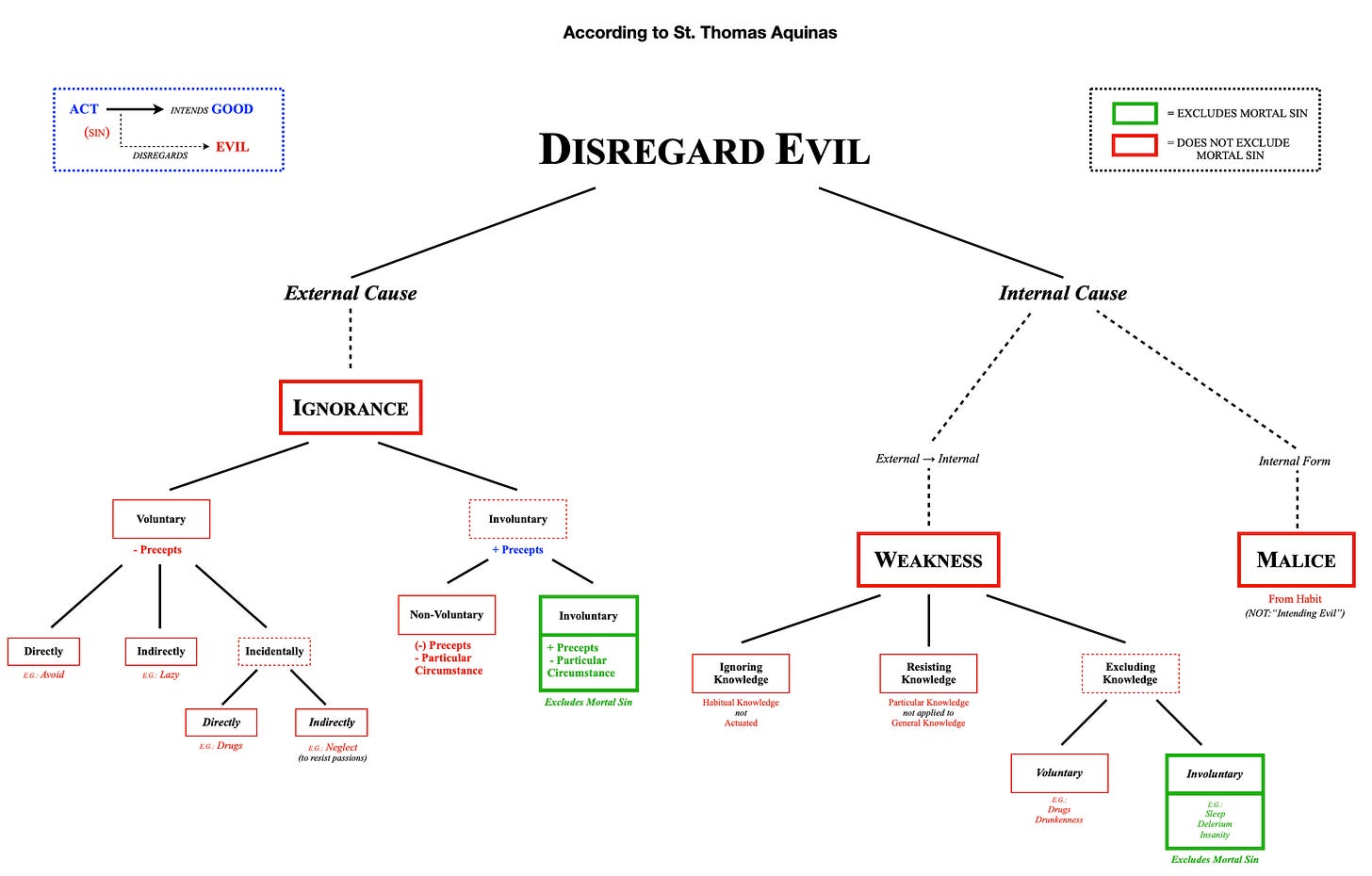

The reason I’d offer is that the same rules that mediate the “imperfection” of a moral act due to ignorance / weakness / malice, mediate conscience. And most people are entirely confused on the distinction between these. They do not have clarity of understanding around the distinction between vincible (culpable) ignorance and invincible (inculpable) ignorance. I’ve presented this chart before, and it’s in my forthcoming book on Mortal Sin, but I’ll represent it here:

These same guidelines qualify conscience—so that if one is inculpably ignorant, not of a law/precept, but of some particular fact, and conscience makes a judgement accordingly, then conscience does have the power to loose. But if a person is culpably ignorant, and conscience makes a judgement, accordingly, then conscience does not have the power to loose. Here’s St. Thomas saying precisely that in multiple places:

When a man sins in making the error itself, a false conscience is not enough to excuse him. This is the case when he makes a mistake about things which he is required to know. However, if the error is about things which he is not required to know, he is excused by his conscience, as is clear when one sins from ignorance of a fact, as when one approaches another’s wife, whom he thinks is his own. (DV:17:3ad4)

When the error itself is not a sin, the conclusion is true, as when the error is due to ignorance of some fact. But, if it is ignorance of a law, the conclusion is wrong because the ignorance itself is a sin. For before a civil judge, also, one who thus appeals to ignorance of a law which he should know is not excused. (DV:17:4ad5)

Why then do I speak of it so simply and straightforwardly? The answer is because these qualifications around culpable/inculpable ignorance apply to the nature of a voluntary act, which precedes the specifications of sins/conscience. Conscience works the way I’ve outlined above—if there is an inculpable error preceding it, it’s not the specification of the nature of conscience that is changed—rather, it is that specification of conscience does not apply there because of the proper imperfection of the act.

I suspect that the majority of our errors around these specific topics of moral philosophy (viz. mortal sin & conscience) spring from the fact that people have failed to properly parse the difference between the thing considered in itself, specifically, and the considerations of the preceding genus that is qualified by the specification.

Once we straighten that out, we see the nature of both mortal sin, and conscience, with much greater clarity and simplicity.

CONSCIENCE: THE HERESY OF OUR TIME

What do most people believe to be the heresy of our time? Answer: Modernism. “Modernism” has been described as the “synthesis of all heresies”. It’s been characterized as the de-supernaturalizing of the faith. 170 and 120 years ago two of the most notable papal documents of our modern world were devoted to addressing the problem of “modernism”, Blessed Pope Pius IX’s Syllabus of Errors, and Saint Pope Pius X’s Pascendi Dominici Gregis (presented in English as “On the Doctrines of the Modernists”). In these seminal documents, these great popes were trying to address a serious problem that was encroaching upon the faithful. The problem, however, was not yet crystallized, and the Church has been broached by even more widespread error around topics of modernism since, not because we weren’t warned about them, but because the categorization was too broad.

Take, for example, the following exhortation of Pope St. Pius X to bishops in Pascendi Dominici Gregis:

“It is also the duty of the bishops to prevent writings infected with Modernism or favourable to it from being read when they have been published, and to hinder their publication when they have not.” (PDG, 50)

He encouraged dioceses to set up “Diocesan Watch Committees” to check for the errors of modernism in writings published in their dioceses. This document was written in 1907—over the next century we would see the amount of published books per year rise to its current level of ~4 million new books every year. Add on top of that the fact that modernists, according to Pope St. Pius X, “employ a very clever artifice, namely, to present their doctrines without order and systematic arrangement into one whole, scattered and disjointed one from another, so as to appear to be in doubt and uncertainty” (PDG, 4), we quickly see that identifying this error is incredibly difficult to do, and no doubt contributes to the fact that the heresy was not stamped out—nor were clear anathemas able to be promulgated about what to look out for.

It’s my view that the heart of all these errors was the error on conscience enumerated above. I do not think that I have a keener eye than Blessed Pius IX or Saint Pius X, but rather that with the passage of time the central error crystalized more clearly and grew more evident. As it was, in 1907, St. Pius X was referring largely to clergy and academics—in todays modern age, it is a vast majority of the lay faithful that are in error around conscience, believing they can support abortion if they want, or if they think fornication, or living together outside of marriage is fine, then their conscience frees them.

THE DEFINITION OF “HERESY”

All of this gets to the heart of what a “heresy” even is?

If you google it, you will read that a heresy is a belief or opinion contrary to orthodox (especially Christian) doctrine.

If you read Hilaire Belloc’s The Great Heresies, you will get a more essential definition of “heresy” like the following:

“Heresy is the dislocation of some complete and self-supporting scheme by the introduction of a novel denial of some essential part therein.” (Belloc, p. 12)

He’ll go on to explain this as so:

“We mean by a ‘complete and self-supporting scheme’ any system of affirmation in physics or mathematics or philosophy or whatnot, the various parts of which are coherent and sustain each other.” (Belloc, p. 12) And: “Heresy means, then, the warping of a system by ‘exception’—by ‘picking out’ one part of the structure—and implies that the scheme is marred by taking away one part of it, denying one part of it, and either leaving the void unfilled or filling it with some new affirmation.” (Belloc, p. 13)

He’ll even rule out possible sources of confusion with the following:

“The denial of a scheme wholesale is not heresy, and has not the creative power of a heresy. It is of the essence of heresy that it leaves standing a great part of the structure it attacks. On this account it can appeal to believers and continues to affect their lives through deflecting them from their original characters.” (Belloc, p. 14).

The essential definition I use for heresy is the following: A heresy is an erroneous idea introduced into the Christian faith that leads to the spiritual deterioration of those who adopt it.

I specify it as relevant to the Christian faith because the Christian faith is totally and perfectly true, so all errors must ultimately be contrary to it. Additionally, if you have an error within your understanding of ultimate truth, it will cause spiritual, psychological, emotional, and relational deterioration in the one who holds it.

MODERNISM VS. ERRONEOUS CONSCIENCE

With these considerations in mind we begin to see why “modernism” fails to pass the more essential test of what a heresy is: it’s a wholesale attack—it seeks to undermine the whole thing; to leave nothing standing; to destroy Christianity altogether. As Belloc said, “the denial of a scheme wholesale is not heresy, and has not the creative power of a heresy. It is of the essence of heresy that it leaves standing a great part of the structure it attacks. On this account it can appeal to believers and continues to affect their lives through deflecting them from their original characters.” So modernism lacks specificity, whereas “conscience” does not.

Further, errors in conscience evidently lead to major spiritual, psychological, emotional and relational deterioration in those who hold to them. The vast majority of Catholics today have a dead faith, wherein they habitually engage in mortal sin and/or endorse mortal sins with their reason. None of these are inculpably ignorant situations—rather, they are ignorances and denials of precepts, not misapplication of particular facts.

Finally, armed with this understanding of “conscience”, it’s very easy to spot the errors and anathematize them. A priest preaching, or theologian teaching, that conscience is absolutely sovereign is in error. A priest preaching, or theologian teaching, that “as long as you follow your conscience you’re good” is in manifest error. A priest preaching, or theologian teaching, something to be a venial sin or no sin that the tradition of the Church has resoundingly established to be mortal sin is in manifest error, and they have no recourse to erroneous notions of “private opinion” or “matters of conscience”.

For all these reasons, I am firmly convinced that the heresy of our time, that which needs to be uprooted entirely from our Catholic faith, is not pertaining to modernism, but to conscience. +

Thank you. There’s much here to think about.

Obviously, this is not for regular people to deal with mortal or venial sin.

The reason why I said this; generally, one does not think whether it is sin or not. People commits sin because they like what they want to do. In their thinking it is beneficial to them.

Here is my proof. Did Eve ever consider if it is mortal or venial sin to eat if the forbidden fruit? No. What she was thinking was how good it is for food, that it is pleasing to the eyes that it will make her wise. Never it came to her mind whether it was venial or mortal.

She knew as well Adam knew they will die. Did that deterred them from eating. No. Knowing whether it is mortal or venial does not keep people from commiting sin.

Hence, the consideration whether mortal or venial is the for judge, the priest,the cannon lawyer to do; not for the regular people.